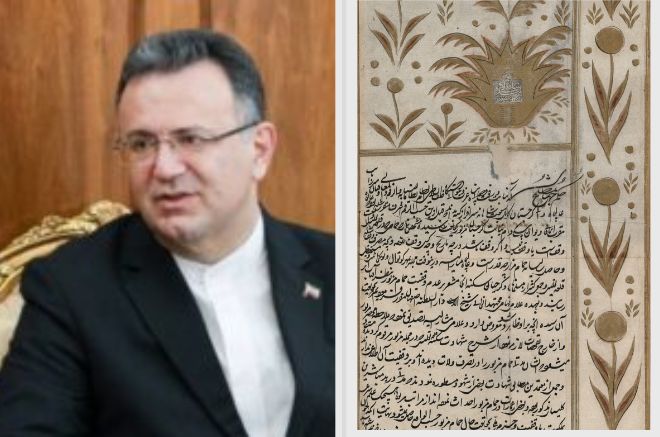

“When Documents Speak Louder Than Politics” – writes the Ambassador of the Islamic Republic of Iran to Georgia, Seyed Ali Mojani.

One of my main interests during the relatively short period of my diplomatic mission in Tbilisi has been the study of the history and archival documents of Iran–Georgia relations. Almost every weekend, I systematically familiarize myself with historical sources. Recently, I completed a renewed examination of a document from the Georgian National Archives dated March 26, 1705, belonging to the Safavid era.

The document concerns a legal dispute related to one of the bathhouses in Tbilisi. The bathhouse had previously belonged to the Georgian Orthodox Church, and the income derived from it was used to support the livelihood of monks in a monastery. At some point, a state official, invoking Islamic waqf motives, transferred the bathhouse into his ownership. The Patriarch of the Georgian Church challenged this action. Following his complaint, the matter was reviewed at the Iranian royal court. The Shiite Shah of the Safavid dynasty, having determined the claim to be unfounded, issued an order from Isfahan that the bathhouse be immediately confiscated from the said individual and returned to the Georgian Orthodox Church, and that its revenues once again be used for church needs according to the previous arrangement.

This example is not presented to evaluate the past, but to emphasize the necessity of a documentary and multidimensional understanding of history. Assessing Safavid rule in Georgia requires serious scholarly research based on authentic sources, as well as joint cooperation between Iranian and Georgian researchers. Only through such an approach is it possible to form a unified, scientific, and reliable narrative and to avoid stereotypes, accusations, and ideological interpretations.

History is not a space for political verdicts; it is a field for understanding human experience within the context of time — an experience shaped simultaneously by geographical and climatic factors, as well as by structures of power. Only by taking these complexities into account can a historian properly perceive the past.

As the Ambassador of the Islamic Republic of Iran to Georgia, and as someone with many years of research experience in the history of Iran and its neighboring countries, I believe the time has come to initiate a deep academic dialogue between our two countries. The creation of joint research mechanisms, particularly historical research committees, would facilitate the systematic study of archives and strengthen a shared historical narrative on a scientific basis.

A documentary and comprehensive understanding of the past is necessary not to repeat traumas, but to raise the awareness of future generations and to strengthen coexistence, social resilience, and cooperation. The future relations between Iran and its neighbors cannot be built on the appropriation of cultural heritage or emotional interpretations of the past; they can only be shaped on the foundation of profound understanding, academic dialogue, and a responsible attitude toward our shared human experience.

If we allow the archives to speak, politics will be compelled to refrain from hasty judgments and submit to historical understanding. This, perhaps, will be the first step toward creating a more rational, humane, and sustainable future in our region.